We will go back in time, back to 1993 when playing Doom on your PC left an everlasting impression and the beat of Haddaways’ new hit song Life made you dance through the soles of your Air Jordans. Life will never be the same, life is changing… are the lyrics to the song. This is somebody’s story, maybe not yours, but several of you might share similar details and most of you were affected by the surrounding cultural context. Our social relations, personal disposition, talk about events, mental state, mind and body are all an integral feature of our emotion discourse (Edwards, 1997). It is the collective emotional standard of the culture we are in, or ‘emotionology’ as proposed by Peter Sterns and Carol Sterns. At this time I was 9 and even though I was not aware of how the world was changing around me, the different cultural contexts I have experienced have still left a lasting imprint on my narration.

The stories that surround us and how we are personally positioned within the various contexts form our world. This world is the sum of our experiences and our cognitive narration, it is our storyworld. Each of us shapes this storyworld through the way we narrate our experiences and memories.

Back in my 1993, in my spatiotemporal setting, we had as a family habit to go for long walks in the forest and along the rocky shores of west coast Finland. Countless sticklike trees limited by the harsh winter conditions, all grown tightly together barely letting any light penetrate the overlapping branches form the Finnish woodlands. A soft moss, like a fitted carpet thick as a mattress, covers much of the ground. Here I am in the dark forest pacing on the cushiony natural carpet and sometimes bouncing forwards towards new experiences. Suddenly the forest would open up and the dim light would change to a view over the sea. For as far as you could see the ground was broken, it looked as if the coast had been pushed through a shredder and then sprinkled all around the sea. As a child this was the sea familiar to me, but now, when revisiting these places it has a slightly unreal feeling to it. I enter into what I could call my Finnish mindset; the rest of the world is isolated, there is only me and the sounds of the leaves in the wind and the water softly playing with the rocks. It is a beautiful present left behind by the ice age that filed the bedrock into the thousands of islands that form the Finnish archipelago.

On these smoothed rock shores you would see the occasional tree growing in most particular ways. The 9 year old me went looking for these strange creations. I have memories of a tree growing out of a small piece of dirt with roots stretching out to other patches of dirt, growing on a big loose rock with the roots hugging around the stone to reach the ground below, curving out of the face of a vertical cliff, or twisted around its own exes shaped like a screw due to the unidirectional wind at the shore. This did not only show me the express adaptability that nature displays, but in a simplistic way how deciding the external relationships are in shaping the trees’ final form.

Effectively each tree starts out as the same, a pinecone will produce a pine. Its DNA defines what the tree is, but how it will grow and what shapes it will take are sculpted by the environmental inputs; rainfall, temperature, winds, nutrition, natural disasters. These are the interactions and the experiences with the world that eventually sculpt the story of each individual tree. In a similar way as us humans define ourselves through our memories, through our shared experiences, the tree is defined through the history stored within it. The growth rings are like archives full of collected and conserved documents of the past. Cutting into a tree we can walk down memory lane and view the life of the tree year by year. Each ring is a summary of events and by reading each of these rings we are presented with the life story of the tree, its autobiography.

The past is represented as layers of stories building up one on top of the other. Each new layer is affected by the sum of all the previous layers, all the previous stories. We as well are shaped by the totality of our experiences, the stories that shape our narrative world.

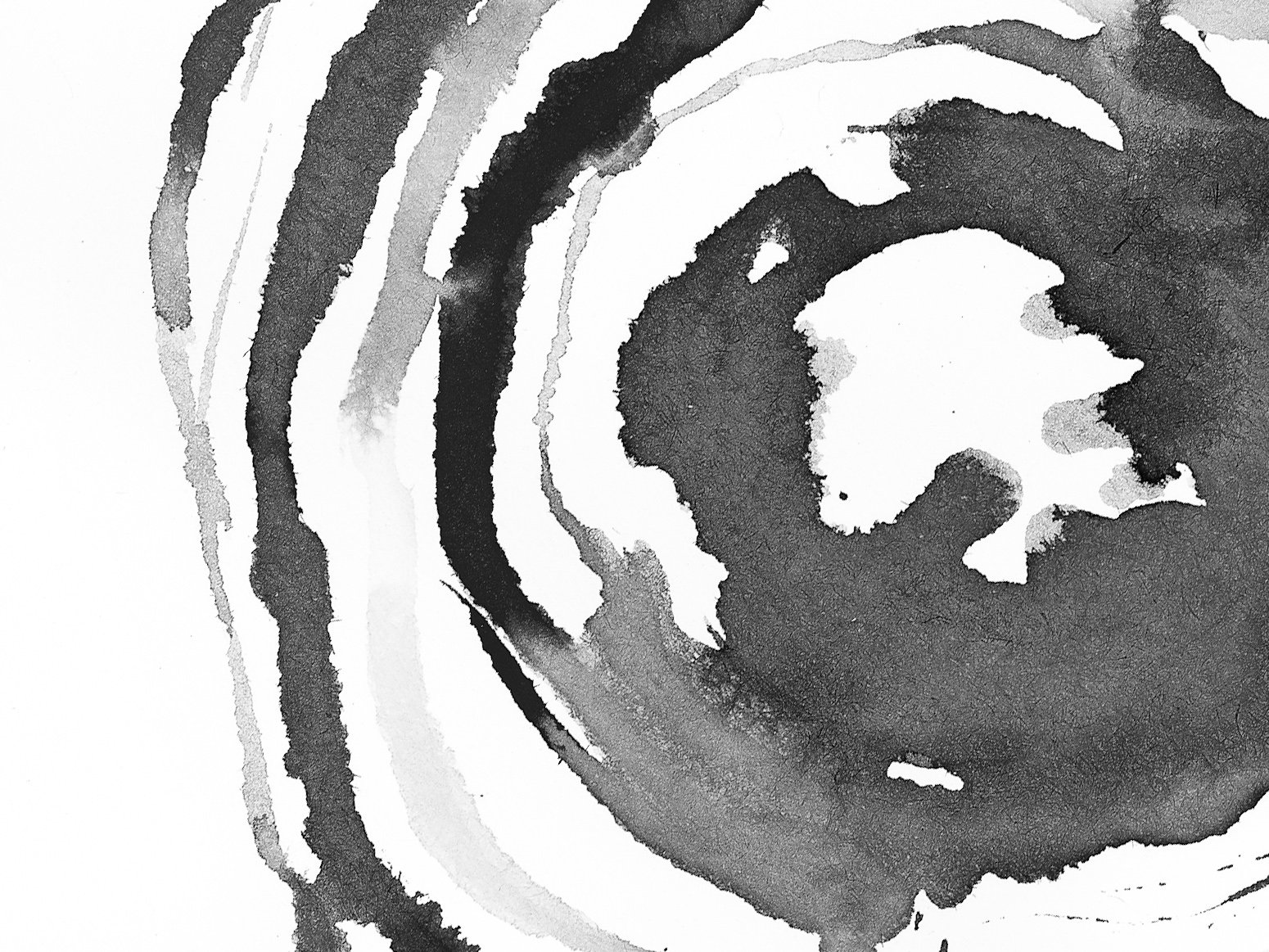

For this study I will accommodate my narration to the principle of growth rings. The different cultures I have been in, changes in the stories surrounding me, the emotionological world I am in, each change leaving a trace, a new ring. This a low bandwidth approach to map my story so I will call this my 8-bit narrative world. This low resolution image of my story will serve as a cognitive script, a map of some sorts, to navigate my storyworld.

Every culture and subculture has an emotionology, which is a framework for conceptualizing emotions, their causes, and how participants in discourse are likely to display them. (Herman, 2011)

These existing frameworks or scripts are the pixels in the low resolution image and together they will form a representation of me. You use these scripts as a way to guide your expectations, a way to fill in the blanks or render more detail into the individual pixel. Let us consider two pixels, two cultural contexts. (a) I am a designer and (b) I grew up, for the most part, in Finland. Now you will consider Nordic design, Scandinavian design, some of you will fill the blanks with Alvar Aalto, curved birch ply while others think of an attitude toward design that reflects a particular view of the environment and the objects that furnish it. Sensible, functional, natural materials, and emphasis on quality and timelessness rather than on trend-setting style. These are words or concepts that might come to mind, they are conceptualized emotions, an approximation of my likely discourse.

A new technology presented by Jack Gallant (UC Berceley) uses a similar methodology to view the images in our mind. Using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) and computational models, people’s dynamic visual experiences can be decoded and reconstructed as images on a screen. You start by measuring the blood flow through the visual cortex while showing a set of video clips. The measurements are then processed by a reconstruction algorithm that uses 18 million seconds of random YouTube videos as a framework, a palette. The algorithm predicts the brain activity that each film clip would most likely evoke in each subject and uses the video clips from the framework to create a blurry yet continuous reconstruction of the original movie. In my 8-bit world, the growth rings are the visual cortex measurements, the frameworks or scripts are the YouTube videos and I am the final image that is created.

Now that we have the tools we can paint my narration, the designers’ story, using a cultural palette as our paint and growth rings as our paintbrush.

An illustration of my narration using the emotionological growth rings. Below you have the legend showing the colours for each culture.